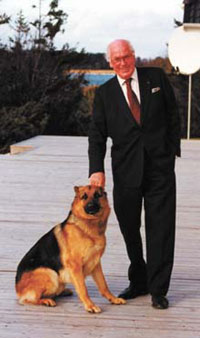

Nearing the end of his second term in office, President Lennart Meri looks back at Estonia’s remarkable economic and political progress in the ten years since independence, and shares his views on the obstacles still ahead, on EU and NATO integration, and on certain American TV shows.

“Do you know Peyton Place?” President of Estonia Lennart Meri asks us. The TV show Peyton Place, he tells us, was his mother’s favorite. The show was just as popular in Estonia in the sixties as it was in America, and the president’s mother used to watch it through broadcast on Finnish TV. “Helsinki was out of our range, but at nighttime, when the television broadcasts started on Finnish TV, we were out of the Soviet Union. We were with the rest of the world when Armstrong took the first steps on the moon. We were with you when President Kennedy was shot. We knew what was going on outside the Iron Curtain. What we didn’t know was the smell of a fresh banana.”

“Do you know Peyton Place?” President of Estonia Lennart Meri asks us. The TV show Peyton Place, he tells us, was his mother’s favorite. The show was just as popular in Estonia in the sixties as it was in America, and the president’s mother used to watch it through broadcast on Finnish TV. “Helsinki was out of our range, but at nighttime, when the television broadcasts started on Finnish TV, we were out of the Soviet Union. We were with the rest of the world when Armstrong took the first steps on the moon. We were with you when President Kennedy was shot. We knew what was going on outside the Iron Curtain. What we didn’t know was the smell of a fresh banana.”

“Finnish television broadcasts meant so much to us when they started in the fifties,” President Meri continues. “They provided us with a window to the world. We saw what they had and we saw what we didn’t have. When we regained our independence we had a very good idea of what we wanted. We wanted to be just like Finland.”

The two countries gained independence around the same time, Finland in 1917 and Estonia in 1918, and Estonia was almost at the same level of economic development as Finland before World War II. While Finland went on to build one of the strongest economies in Europe, Estonia suffered through fifty years of Soviet occupation and has only had a decade to attempt to catch up. (Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union between 1940 - 1991, save four years between 1941 – 1944 when the country was occupied by the Germans.)

In this decade of freedom, the country has accomplished an impressive amount. Nearly all state-owned enterprises have been privatized, and property returned to its rightful owners. Strict monetary and liberal trade policies have spurred a six per cent a year economic growth level. The base of the economy is rapidly changing from agriculture and fisheries to services and high-tech industries. The country has surpassed Italy and France in Internet connectivity, and Estonians are almost up there with the Finns when it comes to Nokias per capita.

The time has now come to turn to social issues. High on the president’s agenda before he retires after two terms in office in August, is caring for the less fortunate Estonians, such as the elderly, and integrating Estonia’s Russian population, close to a third of the total population, into Estonian society.

“We have been successful because we felt we had to secure our future. But you can’t secure your future just pushing social problems aside for a long time. And that’s what we have done for ten years. Now we are approaching a time when we have to take into account that the pensions paid to retirees are very small, and that the life expectancy is not very high. We now are paying the price of having been under a totalitarian system.

” The president knows that totalitarian system very well. When he was nine years old, in 1941, the president and his family were deported to Siberia, and spent four years in exile. Of those years, the president says: “I don’t feel any hate towards those times, or towards Russia. I feel only a deep hate towards the totalitarian system.”

While the president does not dwell in the past, he emphasizes how important it is to remember. “There is always a need to go into the past. Not because the past in interesting, but because we need the past to understand the present. We need to understand why people are so interested in joining NATO for instance. NATO gives a guaranteed feeling of stability, which is, of course, very important for us, having a neighbor like Russia.”

“Russia has always been, in a way, a colonial power,” the president, a scholar in Russian history, continues. “Its power has been reached through long expansions. We don’t have a guarantee that Russia, which has immense natural resources, will develop herself based on an open market and in a democratic way. We simply cannot take the risk of having a stretch of insecurity on the Russian Western border. Russia does produce insecurity. I’m happy that the Western border of Russia has been a perfect border of peace. But that is not a Russian achievement. That is an achievement of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.”

To protect that border, the president strongly favors Estonian accession to the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). “It was clear for us from the beginning that Estonia must become a member of NATO and the EU. Knowing our Soviet past, we knew we had to pay for security.” The Republic of Estonia, independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, is a legal continuation of the independent republic proclaimed in 1918. The United States never acknowledged the Soviet Union’s forcible incorporation of Estonia in 1940, and has always adhered to a policy of non-recognition of Soviet expansion into the Baltic region. When Estonia regained independence in 1991, the United States reinstated diplomatic relations with the country.

The policy of non-recognition was very important to Estonia, not just from a political perspective, but also from a psychological point of view, President Meri explains.

“Although the Baltic issue was not always in focus, certain actions, like the signing of the Helsinki Declaration in 1975, reminded us that the US attitude towards the occupied Baltic States had not changed. And then in 1991 we saw the diplomatic relations with the United States reinstated. It was not the first country to do so, neither the second, nor the twenty-fifth, but the forty-third. But that doesn’t matter. It was already obvious that it would be done.”

It has been ten years since re-independence and the Estonian public school system is full of students who barely remember the country’s Soviet past. The older generation, however, has not forgotten. Illustrating how things have changed, the president says: “Last Sunday I went out to the market. As I walked around, picking out my potatoes, people came up to me and shook my hand. A Russian woman came up. She said ‘I’ve seen Gorbachev and I’ve seen Yeltsin. They were always surrounded by security guards, but you are just shopping as I am, at the market.’ And I answered her ‘why should I be surrounded by guards? This is a free country now.’”